Geoff Badger's quest to bring hidden gems and 'lost' film prints to audiences is keeping the celluloid dream alive.

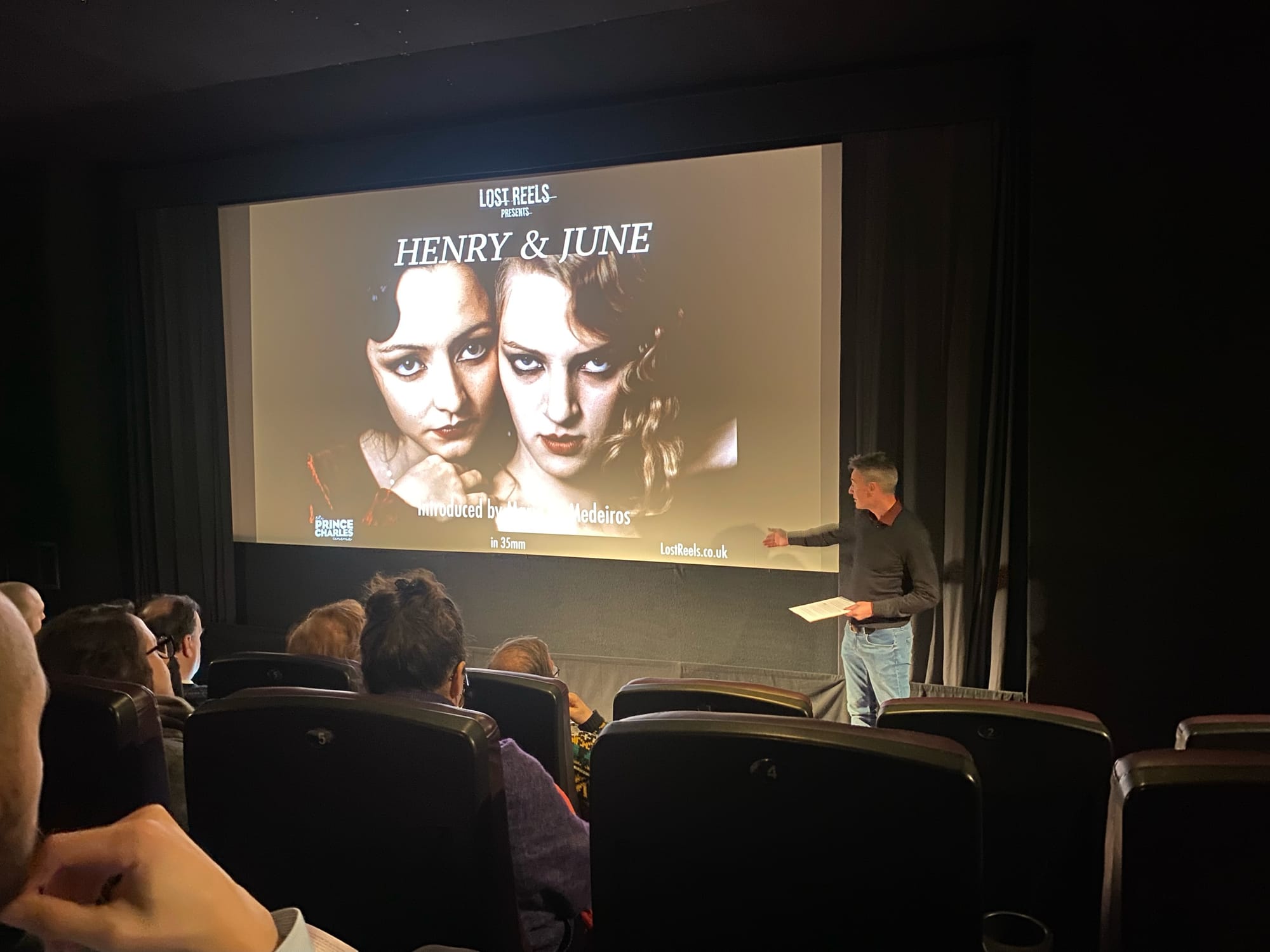

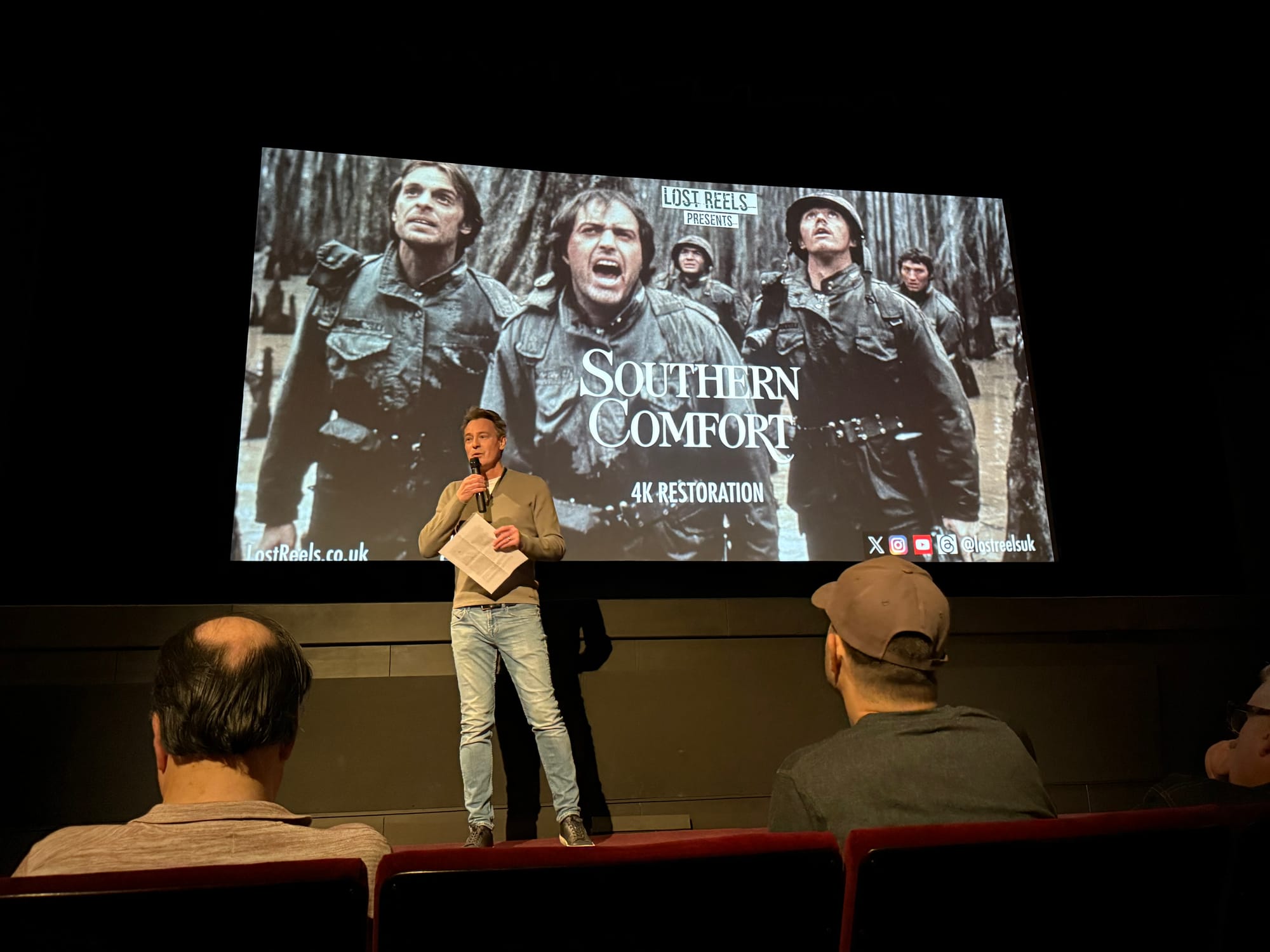

We first came across Lost Reels when TheNeverPress went on a group outing to the wonderful Cinema Museum in Kennington - a beautiful, ramshackle museum run by volunteers dedicated to celebrating the beauty of movies. We were there to see 'The Squeeze', a grimy British crime caper from '77 starring the mighty Stacy Keach. This screening was the first in the Wanted! season of lost British crime films, brought together by Lost Reels.

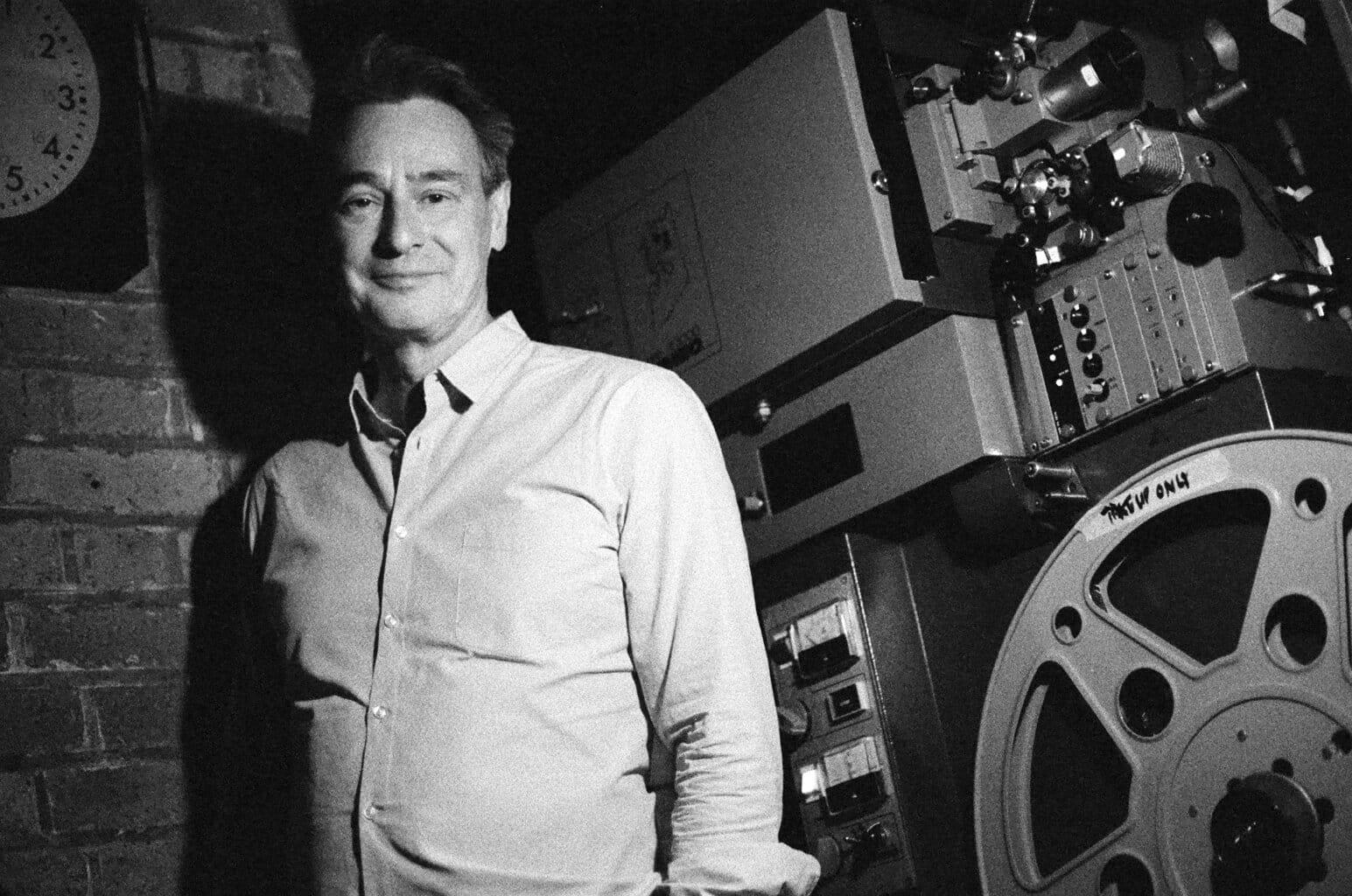

The film (ace by the way) was one thing, but it was the presentation, and care poured into the programme by Lost Reels that really blew us away. Here was a small, independent organisation dedicated to film - to it's preservation, and to presenting it; to letting the art be released from the vaults for new audiences to see. We had to meet the person behind the initiative. And we certainly did - Geoff Badger, founder of Lost Reels, is not only affable, welcoming and genial, he is bursting with enthusiasm and love for the artform and for what he is doing. We're absolutely delighted to bring you this interview with Geoff about his wonderful project, his plans and the beauty of film and filmmaking. Here is a dude that really, really believes...

Geoff, it's such a pleasure to meet you. There is so much to get through so let's start at the beginning - may you please tell us about your journey in getting Lost Reels to where it is currently?

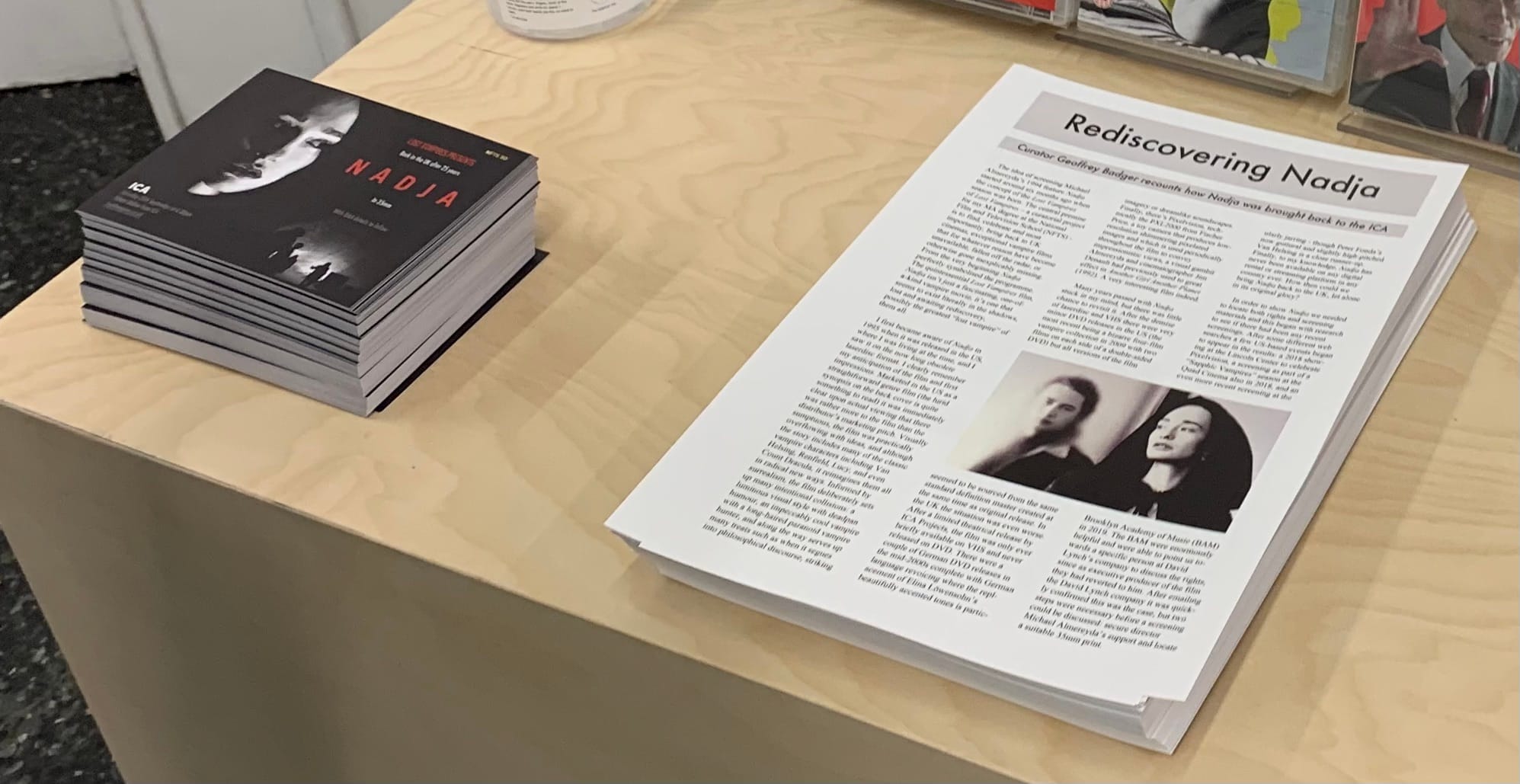

It all started with a film season I developed as part of my Programming and Curation course at the National Film School, called Lost Vampires. One of the titles I selected was an off-the-radar black-and-white avant-garde vampire film called Nadja (1994) produced by David Lynch and directed by Michael Almereyda. In the process of figuring out how to screen this film I discovered the rights were personally owned by David Lynch and the only projectable material in Europe was a 35mm print in Barcelona with Spanish subtitles. Nevertheless I was able to get in touch with David Lynch to obtain the rights and managed to import the print to the UK.

I wrote an essay about this experience and hosted a sold-out screening at The ICA with several cast members participating in a post-screening Q&A. The tremendous response to this event set the framework for Lost Reels and everything evolved from there. I’ve continued to specialise in out-of-circulation films, original prints wherever possible and Q&As, and particularly over the past couple of years I’ve increased the number of screenings. I’m on track for over a dozen films and almost twenty events this year.

What is the ethos of Lost Reels?

The driving philosophy is to revive interesting films that seem to have fallen out of circulation by showing them from original film prints to new and returning audiences. I try to give them the best chance to succeed by partnering with the best venue to attract the film’s potential audience. I also write viewing notes and often create new trailers and posters to market them, particularly when I feel the film wasn’t well-handled on initial release. Each screening is a significant effort, and the amount of work involved means it’s not a commercial proposition. I say Lost Reels is a cultural project not a commercial one, and that’s absolutely true because if I paid myself for the work I do I’d literally be making a few pence an hour.

Why is it important to preserve film?

There’s a set of anthropological, historical, and cultural reasons, but specifically for film there are aesthetic and technical reasons too. The ability of film to display visual images is yet to be matched by digital formats, and as a storage medium - and this may surprise some people - film is more durable and robust than digital. With digital it’s a constant battle to keep pace with evolving formats and there’s a very high risk of storage media degradation or failure. As crazy as it sounds, 35mm film when properly stored, is massively superior to digital as an archival format.

What considerations, challenges and obstacles are there when dealing with old prints

Since I mostly show forgotten or missing films it’s not only an issue of old prints, but old prints that haven’t been out of their cans in decades. Any pre-1982 print is inherently risky because it was manufactured before low fade stocks, and colour fade is always a concern with those. There’s also the question of how the print has been stored, and many prints, even from robust facilities can suffer from what is known as ‘vinegar syndrome’ which is a disastrous chemical decomposition process that renders prints unplayable. Few sources provide detailed print reports so you’re rarely sure of what you’re getting until you actually see it. Finally, if the print has been sourced from an archive then it will be subject to strict handling conditions which will limit the number of venues that can play it, so there are a lot of considerations.

Can you take us through the process of idea to screen? What are the steps and who do you speak to?

I try to differentiate Lost Reels by only showing films no one else is playing, so I always research my ideas to determine whether this is in fact the case. If I discover someone has recently shown a title I move on to something else. Availability on streaming and home media is also a factor – the less available, the more deserving it is of a Lost Reels project. If a title is too little known I run the risk of not finding an audience, so there’s a constant balance between selecting something interesting, but not so obscure no one has ever heard of it. Once I’ve decided to screen a particular title then I determine whether I can obtain the screening rights and what materials are available.

For many films there are no digital materials so I need to find if a print exists and can be obtained. The rights search for a film is normally the longest part of the process in terms of elapsed time and the biggest risk factor. For a non-studio film, the search could go anywhere. I mentioned Nadja where it led to David Lynch, and I often find myself following a trail of bankrupt distributors and subsequent acquisitions to follow a title to its current owner. At times I’ve contacted the legal representatives of the producers and their estates to see if they own the rights. The process for prints is a little more predictable since mostly they come from a more constrained set of sources. When I’ve found and negotiated the rights and settled on my materials then I approach the venue I believe best aligns with the film’s potential audience. The bottom-line is I work through all the rights and materials issues first because until those two requirements are met then there’s no event to pitch.

Sometimes it can take months or years to track down a print, how tenacious do you have to be? At what point do you give up?

Very tenacious! If it’s a situation where there’s no digital copy available the only thing to do is to keep looking. If there’s a good digital alternative and no print available, I try to weigh the cultural benefit of bringing the film back to the public in a less than optimal format against the prospect of not showing it at all. A good example of that is the film I’m showing this Christmas, Keith Gordon’s A Midnight Clear which is simply too good to hold back on due to the lack of a print. The real mission is to bring these films back to the public and sometimes prints simply aren’t available – not just older films but situations such as director’s cuts that have been more recently reassembled and were never released on film. There are always practical issues with prints, including condition and cost, and although I’ve willingly taken financial losses on screenings due to the high expense of particular prints, I can’t do that every time or I’d be out of business. Ninety percent of what I do is from prints and digital is very much the exception, but there are still times when digital is the way to go. So although I’m passionate about the celluloid experience there’s still a balance to be had.

'A Midnight Clear' - Tickets for this Lost Reels presentation at the ICA below

Tell us about tracking down ultra rare prints – how does it feel to have it in your hands?

Nerve-wracking, though they’re rarely in my hands and will almost always go directly to the venue. There are exceptions. When I screened Metropolitan on my Whit Stillman tour I hand-carried the print to the different venues, and when I showed Donald Cammell’s Wild Side I knew it was one of only two 35mm prints in the world, so it was very important to entrust it to an appropriate venue and skilled projectionist.

Is Lost Reels involved in any other activities outside of film exhibition?

I’m something of a champion for the 16mm film format and so I currently have a project with a regional cinema to get their defunct 16mm equipment back into service. I also work on preserving films and prints as a general practice and I’ve been involved in three initiatives now to move prints from insecure storage situations to archives, something that has literally saved them from destruction. I also released a homegrown digital reconstruction of a lost film called Bongo Wolf’s Revenge last year. I’d found partial copies of this very curious film in two different UK archives so I created a complete version from the two fragments and was able to release it using a copyright provision in the UK called an Orphan works license.

What does the future look like for Lost Reels?

I’m thinking a lot about how to scale Lost Reels so I’ve been building relationships to understand the dimensions of that and what could be possible. I embarked on a major experiment this summer which was a Lost Reels 35mm and Q&A tour. I was very fortunate to have built a relationship with the filmmaker Whit Stillman who agreed to accompany me to five regional venues in July where we played his films and did Q&As to mostly sellout audiences. It was really a great experience, and I’d love to do something like that again though it requires a film, a filmmaker, and several venues all to be in sync.

I’ve also been exploring distribution models, for example making all the assets from my screenings – rights, prints, copy, posters and so on – easily available to venues so they can host events without my direct involvement. Another idea is to partner with a programming or distribution organisation to promote Lost Reels titles to venues and provide materials. There’s still a lot to think about and consider, and in the meantime I’ve been planning 2026 which will be distinguished, I hope, by some really special films and Q&A guests. I don’t want to say too much, but I’ve managed to connect with some wonderful filmmakers who are willing to engage with the Lost Reels concept and if all goes to plan you can look forward to some really extraordinary films and events next year. The best news of all is I don’t see any of this slowing down.

There seems to be increasing interest from audiences in uncovering these cinematic gems and seeing them in their original formats, so even if I just keep doing what I’m doing I think the future is going to be very bright.

We're constantly on the look out for new artists, creatives and initiatives to feature in TheNeverZine - so if you are, or know someone who is going their own way and doing their own thing on their own terms and would be a good fit to feature please smash that button below and get in contact. By talking to each other, and sharing our journeys, ideas and insights on creativity, art, mental health and resilience we can all create, share and thrive together. Nice thought that.

PS - Don't forget to subscribe below for more content from TheNeverPress 👇